-

Historical Errors Of The Qur'an: Pharaoh and Haman

Historical Errors Of The Qur'an: Pharaoh and Haman

Assalamu alaykum wa rahamatullahi wa barakatuhu:

1. Introduction

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means- The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 40:36-37]

Controversy has prevailed since the European ‘Renaissance’ regarding the historicity of a certain Haman, who according to the Qur’an, was associated with the court of Pharaoh to whom Moses was sent as a Prophet by God. Haman is mentioned by name six times in the Qur’an and is referred to as an intimate person belonging to the close circle of Pharaoh, one who was engaged in construction projects. Western scholars have concluded that Haman is unknown to ancient Egyptian history. They say that the name Haman is first mentioned in the biblical Book of Esther, around 1,000 years after Pharaoh. The name is said to be Babylonian, not Egyptian. According to the Book of Esther, Haman was a counsellor of Ahasuerus (the biblical name of Xerxes) who was an enemy of the Jews. It has been suggested that Prophet Muhammad mixed biblical stories, namely the Jewish myths of the Tower of Babel and the story of Esther and Moses into a single confused account when composing the Qur’an.

We propose to examine the various aspects of this controversy, primarily grounded in a source-critical analysis along with a literary comparison, in light of modern historical and archaeological research.

2. Hmn According To The Qur’an: A Brief Character Analysis

Haman is mentioned by name in six verses of the Qur’an.[1] From these six verses we can deduce Haman is one of the characters depicted in the confrontation between Moses and Pharaoh, indicating it is this part of the story where the context of Haman can be properly established. Other characters that form part of this narrative are Hrn (Prophet, supporter of Moses) and Qarn. Three other characters, al-Samiri, the unidentified servant and the servant of God, do not play a role in the confrontation though they are part of the larger Moses narrative. One of the most vividly described and oft-repeated head-to-head confrontations in the Qur’an, this story can be found dispersed throughout many srahs. Based primarily on the principal continuous text portions we can indeed discover the Qur’anic Haman, and reach a more useful assessment of his character than simply listing the verses containing his name.

CONFRONTATION BETWEEN MOSES AND PHARAOH

The confrontation between Moses and the Pharaoh is one of the most vividly described stories in the Qur’an, mentioned with details in fifteen srahs.[2] This part of the story begins when God sends Moses to Pharaoh with miraculous signs. After showing Pharaoh his miraculous signs, Pharaoh’s inner circle of leaders become fearful, with Pharaoh accusing Moses of being a learned sorcerer trying to expel him from Egypt by using magic. Consequently, the Pharaoh sets a challenge between Moses and his best magicians to see whose signs are really superior; this event is given added significance as it is to take place on the renowned ‘Day of Celebration’. When the contest takes place and Moses prevails, Pharaoh’s magicians fall prostrate and openly declare their belief in the God of Moses. Pharaoh refused to accept the result of the contest and instead threatens severe punishment to anyone who believes in Moses and his God. Frustrated by Moses’ success and the wavering of his own people, Pharaoh instructs Haman to construct for him a lofty tower so that he can survey the God of Moses, though he is convinced Moses is lying. Thus we can observe it is at this stage of the confrontation that Haman assumes a clearly defined role. Likewise, it is at this point in the story we reach the climax of Pharaoh’s haughtiness and arrogance, who after been given a physical demonstration of miraculous signs and personal reminders from Moses, thinks he is able to survey God as a God. Eventually Pharaoh tried to kill Moses and his followers but instead was drowned as a punishment from God and his body preserved as a sign for future generations.

The main characters in the story are undoubtedly Moses and Pharaoh, protagonist and antagonist, respectively. Though Haman is portrayed as a minor character whose authority and power are clearly secondary to Pharaoh’s, his importance as part of Pharaoh’s court should not be underestimated. Indirectly, Haman’s seniority as part of Pharaoh’s court is mentioned in the story when Moses was sent to Pharaoh and his chiefs with signs but they were rejected [Qur’an 7:103]. Although not mentioned by name in this verse, it is clear that Haman must be considered part of this group and he is one of Pharaoh’s leading supporters. Only snippets of information are given regarding Haman, so one cannot indulge in an all-encompassing discussion regarding his personality, character traits, etc., though what we do learn about him is not unimportant. Haman is given commands and carries them out dutifully. He is put in charge of a very important construction project, indicating he possessed seniority and skill necessary to see the task through to completion, although we are not told anything more about the construction of the tower or if it was even built. He holds a senior enough position to be mentioned along with Pharaoh repeatedly. He was also an accuser, calling Moses a sorcerer and a liar. Haman is portrayed as a highly unethical character; motivated by his hatred towards the believers, and, along with Pharaoh and Qarn, he initiated the slaying of the sons of the believers sparing only their women. Haman’s character is unchanging; he does not acquire any new attributes and is described as a wrongdoer, arrogant and one who commits sins. Haman died perhaps around the same time as the Pharaoh as a punishment from God for his unbelief and tyranny.

3. Criticism And Caution By Western Scholars

Prominent Orientalists have struggled to properly situate the Haman of the Qur’an, and have thus questioned his historicity. They have suggested that the appearance of Haman in the Qur’anic story of Moses and Pharaoh has resulted from a misreading of the Bible, leading the author of the Qur’an to move Haman from the Persian court of King Ahasuerus to the Egyptian court of Pharaoh. The most detailed attempt to draw a genetic connection between the Haman of the Qur’an and the Haman of the Bible has been made by Adam Silverstein,[3] a Fellow of Queens College and University Research Lecturer at the Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford. Silverstein’s attempt to show Haman transitioning from the Bible to the Qur’an is probably the most detailed investigation so far of any character in the Qur’an in relation to its supposed dependence and subsequent transition from its corresponding biblical counterpart. For this reason alone, Silverstein’s article deserves special attention and interaction for the valuable insights it provides.

Modern scholars identify Father Ludovico Marraccio, an Italian monk from Lucca and Confessor to Pope Innocent XI, as the first scholar to make a chronological differentiation between the Haman of the Qur’an and the Haman of the Bible.[4] There is, however, an earlier occurrence that is worthwhile mentioning in that it helps to properly situate the argument, tracing its trajectory from the outset. Some 250 years earlier in Spain around 1450 CE, Pedro de la Cavalleria, a distinguished jurist and apparently a crypto-convert to Christianity from Judaism, finished composing a work entitled Christ’s Zeal against Jews, Saracens, and Infidels. Subsequently Cavalleria was killed in 1461 CE during a period of civil unrest.[5] His work remained largely unknown until it saw publication in Venice in 1592, edited with a fully annotated commentary by the Spanish scholar Martino Alfonso Vivaldo, based at the theological faculty, University of Bologna. Believing Muhammad to have made a glaring mistake in chronology, Cavalleria said,

This madman makes Haman to be contemporary with Pharaoh, surat. XXXIX. which how falsely and ignorantly it is said, all who understand the Holy Scriptures can declare; and he and his Followers, like Beasts, must be silent.[6]

Vivaldo briefly comments on Cavalleria’s statement by pointing out that Haman’s appearance in the Bible is linked with the historical period associated with the Book of Esther.[7] From this point onward, the vast majority of criticism has centred on the chronological disparity between both accounts. Moving forward, let us now look at a representative sample of critical comments from Western scholars.

One of the next writers to enter the list of critics was Marraccio. Published at the end of the 17th century as part of his monumental Latin translation of the Qur’an, he said:

Mahumet has mixed up sacred stories. He took Haman as the adviser of Pharaoh whereas in reality he was an adviser of Ahaseures, King of Persia. He also thought that the Pharaoh ordered construction for him of a lofty tower from the story of the Tower of Babel. It is certain that in the Sacred Scriptures there is no such story of the Pharaoh. Be that as it may, he [Mahumet] has related a most incredible story.[8]

George Sale in his translation of the Qur’an said:

This name is given to Pharaoh's Chief Minister, from which it is generally inferred that Muhammad has here made Haman, the favourite of Ahasueres, King of Persia, and who indisputably lived many ages after Moses, to be that Prophet's contemporary. But how-probable-so-ever this mistake may seem to us, it will be hard, if not impossible to convince a Muhammadan of it.[9]

In what has been hailed as a “classic” article by Theodor Nldeke that was published in the Encyclopdia Britannica in 1891 CE and reprinted several times since, he says:

The most ignorant Jew could never have mistaken Haman (the minister of Ahasuerus) for the minister of the Pharaoh...[10]

Nldeke’s statement is very telling and we will return to it later in our conclusion. While dealing with the “wonderful anachronisms about the old Israelite history” in the Qur’an, Mingana says:

Who then will not be astonished to learn that in the Koran... Haman is given as a minister of Pharaoh, instead of Ahaseurus?[11]

On the mention of Haman in the Qur’an, Henri Lammens states that it is:

"the most glaring anachronism" and is the result of "the confusion between... Haman, minister of King Ahasuerus and the minister of Moses' Pharaoh."[12]

Similar views were also echoed by Josef Horovitz.[13] Charles Torrey believed that Muhammad drew upon the rabbinic legends of the biblical Book of Esther and even adapted the story of the Tower of Babel.[14] After talking about the apparent ‘confusion’ generated by this cobbling together of multiple sources, Arthur Jeffery says about the origin of the word ‘Haman’:

The probabilities are that the word came to the Arabs from Jewish sources.[15]

The Encyclopaedia Of Islam, under "Haman" says:

Haman, name of the person whom the Kur'an associates with Pharaoh, because of a still unexplained confusion with the minister of Ahasuerus in the Biblical book of Esther.[16]

This claim has been repeated again by the Encyclopaedia Of Islam under "Firawn". It says:

As Pharaoh's counsellor there appears a certain Haman who is responsible in particular for building a tower which will enable Pharaoh to reach the God of Moses... the narrative in Exodus is thus modified in two respects, by misplaced recollection of both the book of Esther and the story of the tower of Babel (Genesis, xi) to which no other reference occurs in the Kur'an.[17]

Consequently, it is not surprising to find Christian apologists, missionaries[18] and other polemicists such as Ibn Warraq[19] exploiting these comments in order to ‘prove’ that the Qur’an contains serious contradictions, being one of the most ‘celebrated’ amongst the Christian missionaries on the internet. Have such criticisms permeated the discussion from the outset? Interestingly, beginning around the turn of the 18th century, some Western scholars were already advising caution.

AN ARGUMENT OF STRAW

Do two people having the same name in different historical periods necessitate a relationship? For the first time, towards the end of the 17th century and the beginning the 18th century, a few Western scholars began to recognise the myths and misconceptions propagated by their academic fellows concerning Islamic beliefs and practices did not stand up to scrutiny under examination, and realised that one needed to come to terms with Islam as a religion in its own right. The first scholar in Europe attempting to do so in a systematic fashion was Adriaan Reland, who from 1701 onwards was Professor of Oriental languages in the University of Utrecht. Known as his most famous work, the second part of De Religione Mohammedica Libri Duo responded to forty-one ‘common misconceptions’ held by his contemporaries and those who preceded him.[20] Section 21 is titled, ‘Concerning Haman that was contemporary with Pharaoh’. We will quote the relevant analysis of Reland so we can properly appreciate the jist of his argument, which, in its basic outline, remains the same today. He said,

I confess, we may believe, if we please, that Mahomet thought Haman (of whom we read in the book of Esther) liv’d in the time of Pharaoh. But we are under no necessity to believe this, unless from the sole Opinion we have of Mahomet’s gross ignorance. Much less can we demonstrate that Mahomet, when he makes Haman and Pharaoh Contemporary, meant the Haman in our Bible. How just, I beseech you, is that Consequence, and how fit to repel the Turks! Because Mahomet speaks of Haman, cap. 29. Therefore he speaks of that Haman whom our Bible mentions. Who does not see this is an Argument of Straw?[21]

One should be careful not to romanticise Reland’s approach. His outlook was quite simple and admirable in terms of the forthright fashion this accomplished scholar set out his overall intention. Such openness as the kind practised by Reland is rarely glimpsed in present-day academia with all its modern pressures. Instead of fighting a set of misconceptions, Reland believed it was only by understanding Islam on its own terms that Christianity could triumph. Finishing off Section 21 he says, “But what I have said is sufficient for my purpose; and is only intended to make our Writers more wary, that the Authority of the Alcoran may be beat down only with valid Reasonings, and the Truth of Christianity may triumph.”[22] Despite these theological concerns, Reland is at least successful in highlighting the potential pitfalls in viewing Islam, the Qur’an and Muhammad exclusively through the prism of earlier biblical tradition. Breaking with the trend of seeing Haman as simply misappropriated from its biblical context, the Encyclopaedia Of The Qur'an makes an intriguing suggestion about the possible identity of Haman,

There are conflicting views as to Haman's identity and the meaning of his name. Among them is that he is the minister of King Ahasuerus who has been shifted, anachronistically, from the Persian empire to the palace of Pharaoh... Other suggestion is that Haman is an Arabized echo of the Egyptian Ha-Amen, the title of a high priest second only in rank to Pharaoh.[23]

Unfortunately no evidence is offered for this suggestion and one is instead directed to the bibliography in a search for answers. Let us first examine the authenticity and historical reliability of the biblical Book of Esther from where Muhammad supposedly appropriated the character of Haman.

4. A Critical Examination Of The Biblical Evidence Used Against The Qur’an

Weighing up the statements given in the previous section from Christian and Jewish scholars, to other less well-known categories of critics such as Christian missionaries, apologists and polemicists, with contributions ranging in type, from scholarly monographs to detailed encyclopaedia entries, their criticisms can be encapsulated on the basis of the following three assumptions:

Because the Bible has been in existence longer than the Qur’an, the biblical account is the correct one, as opposed to the Qur’anic account, which is necessarily inaccurate and false.

The Bible is in conformity with firmly established secular knowledge, whereas the Qur’an contains certain incompatibilities.

Muhammad copied and in some cases altered the biblical material when composing the Qur’an.

It goes without saying those writers who ground their objections in some or all of the assumptions stated above, the whole basis for the Haman controversy is the appearance of a Haman in the Qur’an in a historical period different from that of the Bible. The claim that the Qur’anic account of Haman reflects confused knowledge of the biblical story of Esther implies that any reference to a Haman must have biblical precursors. Furthermore, this assumption itself implies that either Haman is an unhistorical figure that never existed outside the Bible, or that if he was historical, then he could only have been the Prime Minister of the Persian King Ahasuerus, as depicted in the Book of Esther. Unsurprisingly, their assumptions obviously preclude the possibility that the Bible has its information wrong concerning Haman. Thus, only if the Book of Esther can be shown to be both historically reliable and accurate, can those writers be justified in making the claim the Qur’an contradicts the earlier, more “reliable” historical biblical account.

It will come as a welcome surprise to many that not everyone who has written about this topic predicates their arguments on some or all of the assumptions stated above.[24] Nevertheless, as these assumptions continue to permeate the academic discussion regarding this particular topic, it seems justified for one to examine just how much substance should be attached to the biblical evidence, grounded first and foremost in an enquiry into the historicity of the Book of Esther.

THE HISTORICITY OF THE BOOK OF ESTHER AND ITS CHARACTERS

Does the Book of Esther and the characters present in it have any historicity? Whatever side of the debate one finds himself or herself on, it is a fundamentally important question, an issue which has not been tackled by those claimants whose implicit assumptions rule out the possibility that the biblical story of Esther contains historical errors, even though such a position leads to a circular argument. That Jewish and Christian scholars have denied the historicity of the Book of Esther is something of an understatement. It would appear the people who subscribe to the full historicity of the Book of Esther are those whose dogmatic approach to historical and theological exegesis precludes the possibility of any historical problems arising from the biblical narrative. Believing ones holy book to be infallible is of course a mainstream belief found in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. But what happens when such beliefs do not square with commonly accepted ‘historical facts’? While discussing the historical problems of the Book of Esther, Professor Jon Levenson, Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies at the Harvard Divinity School, says:

Even if we make this questionable adjustment, the historical problems with Esther are so massive as to persuade anyone who is not already obligated by religious dogma to believe in the historicity of the biblical narrative to doubt the veracity of the narrative.[25]

Naturally this statement does not sit comfortably with those who have used the Book of Esther to substantiate the historical “contradiction” in the Qur’anic account of Haman. Many scholars have dealt with the problems regarding the historicity of the Book of Esther. Michael Fox, Professor of Hebrew at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who also specialises in Egyptian literature and its relationship with biblical literature, has detailed the arguments for and against the book’s historicity.[26] Fox mentions numerous inaccuracies, implausibilities and outright impossibilities in this biblical book. After considering the arguments in detail, Fox concludes with the following negative assessment:

Various legendary qualities as well as several inaccuracies and implausibilities immediately throw doubt on the book's historicity and give the impression of a writer recalling vaguely remembered past.[27]

Similar assessments were made by Lewis Paton[28] and Carey Moore[29] and they both arrived at the same conclusion that the story in the Book of Esther is not historical. The views of Judaeo-Christian scholars concerning the historicity of the Book of Esther and its characters have been succinctly described by Adele Berlin, one of the editors of the Jewish Study Bible. She said,

Very few twentieth-century Bible scholars believed in the historicity of the book of Esther, but they certainly expended a lot of effort justifying their position. Lewis Bayles Paton, in 1908, wrote fourteen pages outlining the arguments for and against historicity and concluded that the book is not historical. In 1971 Carey A. Moore devoted eleven pages to the issue and arrived at the same conclusion. In more recent commentaries, those of Michael V. Fox in 1991 and Jon D. Levenson in 1997, we find nine and five pages respectively, with both authors agreeing that the book is fictional. You might notice that the number of pages is going down, probably because all the main points were laid out by Paton, and if you are going to rehash an argument you should do it in fewer pages than the original.[30]

With this in mind, it is therefore not our intention to ‘rehash’ every single detail, but rather highlight some beneficial summaries taken from a variety of biblical commentaries, Jewish and Christian (Protestant and Catholic) that form part of the historical enquiry into Esther and its characters. We can thus come to terms with some of the key data the aforementioned scholars interacted with before delivering their assessment.

The Universal Jewish Encyclopaedia, under "Esther", says:

The majority of scholars, however, regard the book as a romance reflecting the customs of later times and given an ancient setting to avoid giving offence. They point out that the 127 provinces mentioned are in strange contrast to the historical twenty Persian Satrapies; that it is astonishing that while Mordecai is known to be a Jew, his ward and cousin, Esther, can conceal the fact that she is a Jewess - that the known queen of Xerxes, Amestris, can be identified with neither Vashti nor Esther; that it would have been impossible for a non-Persian person to be appointed prime minister or for a queen to be selected except from the seven highest noble families; that Mordecai's ready access to the palaces is not in consonance with the strictness with which the Persian harems were guarded; that the laws of Medes and Persians were never irrevocable; and that the state of affairs in the book, amounting practically in civil war, could not have passed unnoticed by historians if this had actually occurred. The very tone of the book itself, its literary craftsmanship and the aptness of its situations, point rather to a romantic story than a historical chronicle.

Some scholars even trace it to a non-Jewish origin entirely; it is, in their opinion, either a reworking of a triumph of the Babylonian gods Marduk (Mordecai) and Ishtar (Esther) over the Elamite gods Humman (Haman) and Mashti (Vashti), or of the suppression of the Magians by Darius I, or even the resistance of the Babylonians to the decree of Artaxerxes II. According to this view, Purim is a Babylonian feast which was taken over by the Jews, and the story of which was given a Jewish colouring.[31]

Published about one hundred years ago, The Jewish Encyclopaedia already asserted that,

Comparatively few modern scholars of note consider the narrative of Esther to rest on a historical foundation... The vast majority of modern expositors have reached the conclusion that the book is a piece of pure fiction, although some writers qualify their criticism by an attempt to treat it as a historical romance.[32]

The more recent Jewish Publication Society Bible Commentary is quite frank about the exaggeration and the lack of historicity of the story in the biblical Book of Esther. It labels the story in the Book of Esther as a “farce”:

The language, like the story, is full of exaggeration and contributes to the sense of excess. There are exaggerated numbers (127 provinces, a 180-day party, a 12-month beauty preparation, Haman's offer of 10,000 talents of silver, a stake 50 cubits high, 75,000 enemy dead)... Esther's attempt to sound like a historical work is tongue in cheek and not to be taken at face value. The author was not trying to write history, or to convince his audience of the historicity of his story (although later readers certainly took it this way). He is, rather, offering a burlesque of historiography... The archival style, like the verbal style, make the story sound big and fancy, official and impertinent at the same time - and this is exactly the effect that is required for such a book. All these stylistic features reinforce the sense that the story is a farce.[33]

The Peake's Commentary On The Bible discusses the historicity of the characters and events mentioned in the Book of Esther. It describes the book as a novel with no historical basis. Furthermore, it deals with the possible identification of Esther, Haman, Vashti and Mordecai with the Babylonian and Elamite gods and goddess.

The story is set in the city of Susa in the reign of Akhashwerosh, king of Persia and Media. This name is now prove to refer to Xerxes, who reigned over Media as well as Persia. The book correctly states that his empire extended from India to Ethiopia, a fact which may well have been remembered long afterwards, especially by someone living in the East, but in other matters the author is inaccurate, for instance in regard to the number of provinces. Xerxes' wife was named Amestris, and not either Vashti or Esther. The statement in Est. 1:19 and 8:5 that the laws of Persia were unalterable is also found in Dan. 6:9, 13. It is not attested by any other early evidence, and seems most unlikely. The most probable suggestion is that it was invented by the author of Daniel to form an essential part of his dramatic story, and afterwards copied by the author of Esther.

It is therefore agreed by all modern scholars that Esther was written long after the time of Xerxes as a novel, with no historical basis, but set for the author's purposes in a time long past. It is pretty clear that the author's purpose was to provide an historical origin for the feast of Purim, which the Jews living somewhere in the East had adopted as a secular carnival. This feast and its mythology are now recognised as being of Babylonian origin. Mordecai represents Marduk, the chief Babylonian God. His cousin Esther represents Ishtar, the chief Babylonian Goddess, who was the cousin of Marduk. Other names are not so obvious, but there was an Elamite God Humman or Humban, and Elamite Goddess Mashti. These names may lie behind Haman and Vashti. One may well imagine that the Babylonian festival enacted a struggle between the Babylonian gods on the one hand and the Elamite gods on the other.[34]

The authors of The New Interpreter's Bible, like the other writers that we have mentioned earlier, state that the biblical Book of Esther is work of fiction that happens to contain some historical elements. It then lists many factual errors only to conclude that the Book of Esther is not a historical record.

Although much ink has been spilled in attempting to show that Esther, or some parts of it is historical, it is clear that the book is a work of fiction that happens to contain some historical elements. The historical elements may be summarized as follows: Xerxes, identified as Ahaseurus, was a "great king" whose empire extended from the borders of India to the borders of Ethiopia. One of the four Persians capitals was located as Susa (the other three being Babylon, Ecbatana, and Persepolis). Non-Persians could attain to high office in the Persian court (witness Nehemiah), and the Persian empire consisted of a wide variety of peoples and ethnic groups. The author also displays a vague familiarity with the geography of Susa, knowing, for example, that the court was separate from the city itself. Here, however, the author's historical veracity ends. Among the factual errors found in the book we may list these: Xerxes' queen was Amestris, to whom he was married throughout his reign; there is no record of a Haman or a Mordecai (or, indeed, of any non-Persian) as second to Xerxes at any time; there is no record of a great massacre in which thousands of the people were killed at any point in Xerxes' reign. The book of Esther is not a historical record, even though its author may have wished to present it as history...[35]

Compiled by Roman Catholic scholars, The Jerome Biblical Commentary brands the Book of Esther as a “fictitious story” that was freely embellished and modified in the course of its transmissional history.

Literary Form. On this point, scholarly opinion ranges from pure myth to strict history. Most critics, however, favor a middle course of historical elements with more or less generous historical embellishments... The Greek additions in particular appear to be essentially literary creations. That neither author intended to write strict history seems obvious from the historical inaccuracies, unusual coincidences, and other traits characteristic of folklore... On the other hand, there is no compelling reason for denying the possibility of an undetermined historical nucleus, and the author's generally accurate picture of Persian life tends to support this possibility. Several details of Est [i.e., Esther] suggest a fictitious story. The very fact of variations between the Hebrew and the deuterocanonical additions show that the book was freely embellished in the course of its history. Then there are many difficulties concerning Mordecai's age, and the wife of Xerxes (Amestris). Moreover, the artificial symmetry suggests fiction: Gentile against Jews; Vashti as opposed to Esther; the hanging of Haman and the appointment of Mordecai as the vizier; the anti-Semitic pogrom and the slaying of the gentiles. A law of contrasts is obviously at work... As is stands, it has been developed very freely as the "festal legend" of a Feast of Purim, which is itself otherwise unknown to us.[36]

A New Catholic Commentary On Holy Scripture points out that the book is given credence only by those who believe that since the Book of Esther is a biblical book, it must be true. It then goes on to wonder if there is any significance in the similarity between the names mentioned in the Book of Esther and the Babylonian and Elamite gods and goddess.

To what extent the story of Esther is factual is debated. On the face of it, not many people would give much credence to Est [i.e., Esther] as history but for the fact that it is a biblical book and 'the Bible is true'. The evidence we have suggests that we have a tale set against an historical background, embodying at least one historical character (Xerxes) and some accurate references to actual usages of Persia, but a tale making no serious attempt to chronicle facts, aiming rather at producing certain moral attitude in the reader... Yet it appears that Xerxes' queen was neither Vashti nor Esther but Amestris; we have no further information inside or outside the Bible (e.g. Sir 44ff) of a Jewish queen who saved her people or of a pious Mordecai who rose to such heights in the Persian court... One may wonder whether there is a significance in the similarity between the name Esther and the name of the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, between the name Mordecai and the name of the god Marduk, so that one would have to look for the source of the tale among the myths of Elamite gods. But one can only wonder.[37]

From the foregoing material, it is clear that Judeo-Christian scholars do not consider the story to be a genuine historical narrative, and of little or no historical value. Furthermore, no scholar claimed that the character Haman actually ever existed. In fact, all characters in the Book of Esther, with perhaps the exception of Ahasuerus, are unknown to history even though the book itself claims that its events are “written in the Book of the Chronicles of the kings of Media and Persia” [Esther 10:2]. Though there are some conservative scholars who argue for some form or even full historical basis for Esther and/or its characters,[38] their analyses have generally not been persuasive.[39] The bewildering variety of literary genres assigned to this book adds to the confusion. How is this book to be read? Most scholars describe Esther as a historicised novel / diaspora novel, or something similar. Levenson reminds us, “This is not to say that the book is false, only that its truth, like the truth of any piece of literature, is relative to its genre, and the genre of Esther is not that of the historical annal (though it sometimes imitates the style of a historical annal).”[40] Ensuring the literary genre reaches an appropriate category is the means by which some scholars soften the serious historical problems and exaggerations, as they seek to argue Esther should not be read as a strict historical narrative but rather, for example, as a heroic-comic narrative[41] or some other similar literary classification.

Concerning the character Haman, the Encyclopaedia Judaica states:

Various explanations have been offered to explain the name and designation of the would-be exterminator of the Jews. The names of both Haman and his father have been associated with haoma, a sacred drink used in Mithraic worship, and with the Elamite god Humman. The name Haman has also been related to the Persian hamayun, 'illustrious', and to the Persian name Owanes.[42]

The Interpreter's Dictionary Of The Bible shares a similar view:

Some scholars view the story of Esther as reflecting a mythological struggle between the gods of Babylon and Elam, with Haman identified as the Elamite god Humman.[43]

As for Ahasuerus in the Book of Esther, he is usually identified with King Xerxes I, King of Persia (486-465 BCE). The Webster's Biographical Dictionary informs us that:

Ahasuerus: Name as used in the Bible, of two unidentified kings of Persia: (1) the great king whose capital was Shushan, modern Susa, sometimes identified with Xerxes the Great, but chronological and other data conflict; (2) the father of Darius the Mede.[44]

There exists an unhistorical Haman in the Book of Esther. This unhistorical Haman is portrayed as the Prime Minister of Ahasuerus (Xerxes I?), King of Persia. Though the author shows familiarity and knowledge of Persian life and courtly customs, the events recorded in the Book of Esther show little correlation with those of the actual reign of Xerxes I. Long ago theologians both Jewish and Christian, had a difficult time accepting the Book of Esther whose canonicity was held in low esteem, especially in the east among early Christians.

ÊÍãóøáÊõ æÍÏíó ãÜÇ áÇ ÃõØíÜÞú ãä ÇáÅÛÊÑÇÈö æåóÜãöø ÇáØÑíÜÞú

Çááåã Çäí ÇÓÇáß Ýí åÐå ÇáÓÇÚÉ Çä ßÇäÊ ÌæáíÇä Ýí ÓÑæÑ ÝÒÏåÇ Ýí ÓÑæÑåÇ æãä äÚíãß ÚáíåÇ . æÇä ßÇäÊ ÌæáíÇä Ýí ÚÐÇÈ ÝäÌåÇ ãä ÚÐÇÈß æÇäÊ ÇáÛäí ÇáÍãíÏ ÈÑÍãÊß íÇ ÇÑÍã ÇáÑÇÍãíä

-

THE TEXTUAL STABILITY AND CANONICITY OF ESTHER

A quick glance at the comments of Western scholars critical of the Haman episode detailed in the Qur’an, show they either explicitly state or implicitly assume the story narrated by the Book of Esther was ‘fixed’ centuries before the Qur’an was written down. Opening up his discussion on the significance of the question Silverstein says, “Although the historicity of the Book of Esther has been rightly challenged by scholars for centuries, it is clear that the Biblical story – even if it is but a historical novella – was fixed centuries before the Qur’n came into existence.”[45] If this statement is to be understood as a comment on the textual quality of Esther then by no means can it be described as ‘fixed’. Should ‘fixed’ be taken to mean the story as represented by the Book of Esther was in existence centuries before the Qur’an then this is of course quite true. So just how has Esther been transmitted to us?

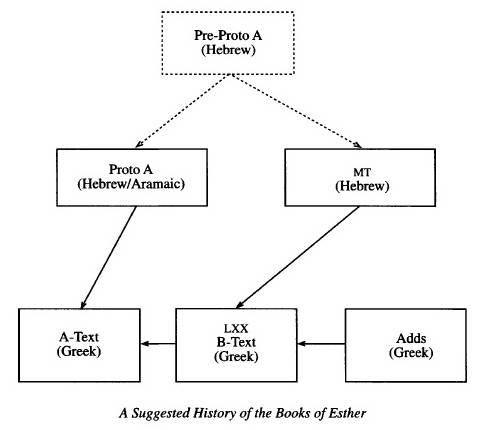

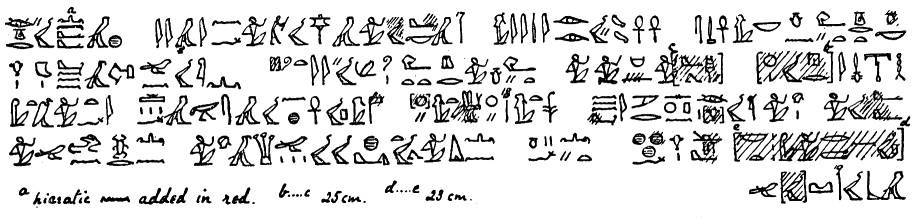

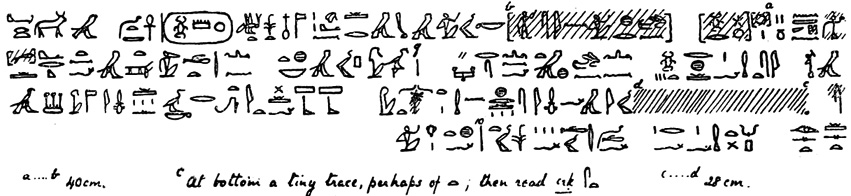

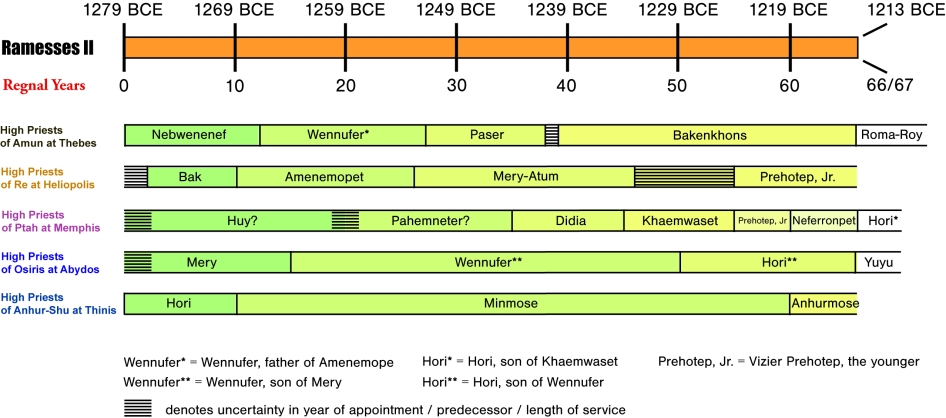

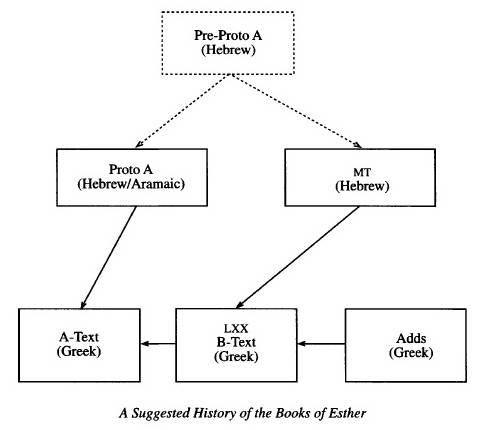

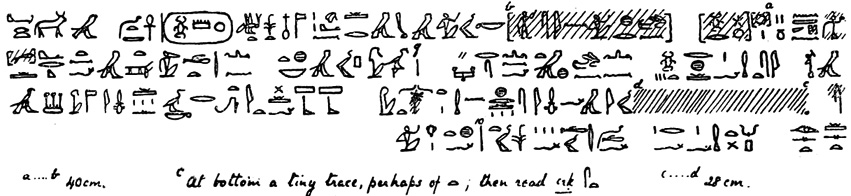

Believed to have been composed around the 4th century to 3rd century BCE (i.e., late Persian to early Hellenistic period),[46] there are three distinct textual versions of Esther extant today, the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT), the Greek LXX (known as B-text) and a second Greek text (known as A-text). The B-text is a free / paraphrased translation of the text represented by the Hebrew MT with an additional six substantial additions (known as Adds A-F). Among the topics included in these six additions are the text of the letters of Haman and Mordecai and the long prayers of Esther and Mordecai. There are also a number of other minor omissions and additions, some that contradict the Hebrew MT. The A-text is similar to the B-text containing the same six additions; however, the A-text is 29% shorter than the B-text and matters are further complicated as the A-text has material not contained in the B-text. Due to these differences some scholars believe the A-text is translated from a Hebrew text different from the text represented by the Hebrew MT. Others propose the B-text is the primary source of the A-text.[47] To visualise these additions in terms of numbers, Hebrew MT Esther contains 3,044 words, the A-text 4,761 words and the B-text 5,837 words. In percentage terms, the A-text is 56.41% longer and the B-text 91.75% longer than the Hebrew MT. Adjusting these percentages to recognise the language differentiation, the A-text is around 45% longer and the B-text 77% longer.[48] The earliest extant manuscript attesting to any of the versions of Esther is a Greek papyrus fragment generally agreeing with the B-text, datable to the late first or early second century CE.[49] What historical circumstances brought about these additions? Ancient Jewish scribes troubled by the lack of religiosity and otherwise overtly secular nature of the book, decided to add more than one hundred verses to the text, interspersed in the beginning, middle and end of the book – within the first ten verses of the two Greek versions of Esther there is a cry to God for help.[50] The inclusion of a multiplicity of theological maxims and the repeated mention God (over fifty times) is significant as the Hebrew MT version of Esther makes no mention of God whatsoever, or indeed any specifically religious practice with perhaps the exception of fasting.[51] These additions which do not appear in the extant Hebrew text are accepted as canonical in the Roman Catholic Bibles (and many others) while Protestant Bibles reject them as apocryphal.

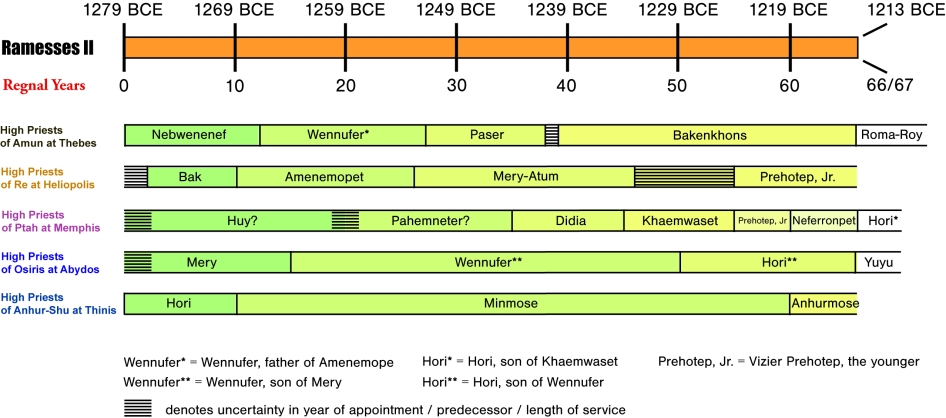

Figure 1: A suggested history of the Books of Esther.[52]

The Proto A and Pre-Proto A posited by Fried are meant to establish where the “Ur-Text” resides [Figure 1]; they do not exist in documentary form. It is important to remember though that the three versions that have been discussed so far are based on real documents and have not been conjectured. Therefore, from the standpoint of its textual transmission, it is clear that the text of Esther has never been ‘fixed’, existing today in different versions.[53] Proceeding from Esther’s fluid transmissional history, early Jews and Christians were led to dispute its canonicity.

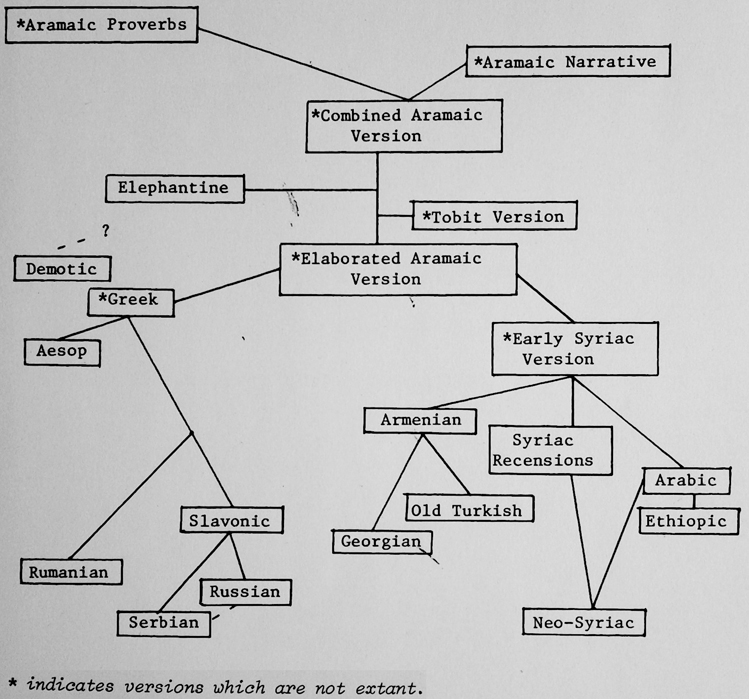

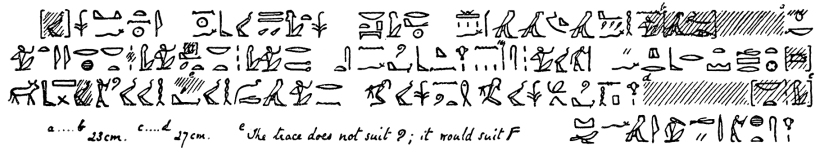

The Book of Esther, which is now regarded by Jews and Christians as canonical, has been embroiled in dispute until the present day. From antiquity onwards its canonicity was hotly contested by members of both religions and their sub-sects. The Book of Esther was evidently not used by the Jewish community in Qumran – being the only book of the Old Testament to be unrepresented in the manuscripts – neither is there any evidence the Purim festival initiated by it was celebrated.[54] According to the Talmud, as late as 3rd or 4th century CE, some Jews still did not regard Esther as canonical.[55] This lack of unanimity regarding the canonical status of Esther was not limited to the Jewish community only, witnessed by similar disputes flaring in Christian circles as well. Figure 2 depicts the canonical status of Esther in the early Christian church.

Figure 2: Map showing the canonical status of Esther in the early Christian Church.[56] Notice that the Book of Esther was considered non-canonical in Constantinople, Sardis, Iconium, Nazianzus, Mopsuestia and Alexandria. On the other hand, Esther was considered canonical in Rome, Hippo, Carthage, Damascus, Caesarea, Jerusalem, Constanti and Constantinople. There appears to be two views of the books canonicity at Constantinople.

From the above figure, it can be seen that in the West, Esther was nearly always canonical, while in the East very often it was not. Among the Christians in the East, especially those in the area of Anatolia (in modern day Turkey) and Syria, the Book of Esther was often denied canonical status. This is confirmed by studying the list of canonical books by Melito of Sardis (c. 170 CE), Gregory of Nazianzus (d. 390 CE), Junilius (c. 550 CE) and Nicephorus (d. 828 CE). While denying the canonical status of Esther, Athanasius (c. 367 CE) did include it with the Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Sirach, Judith and Tobit for catechetical reading. Amphilochius (d. 394 CE) observed that it was accepted only by some. However, as has been noted, in the West, Esther was almost always regarded as canonical. It was accepted by Hilary (c. 360 CE), Augustine (c. 395 CE), Innocent I (c. 405 CE), Rufinus (d. 410 CE), Decree of Gelasius (c. 500 CE), Cassiodorus (c. 560 CE) and Isidorus (d. 636 CE). Esther was also present in the list of Cheltenham canon (c. 360 CE) and codex Claromontanus (c. 350 CE). This book was also endorsed as canonical in the council of Carthage (c. 397 CE).

During the Reformation, the Canon of the Bible, both Old and New Testaments, was called into question. Generally, the Protestants disputed the Catholic claim to interpret scripture, either by Papal decree or by the action of Church councils. Martin Luther (1483 – 1546 CE), one of the Protestant reformers, said concerning the Book of Esther:

I am so great an enemy to the second book of Maccabees, and to Esther, that I wish they had not come to us at all, for they have too many heathen unnaturalities.[57]

Luther’s position appeared to have been wavering concerning the Book of Esther. Andres Bodenstein von Karlstadt (c. 1480 – 1541 CE), an early friend and fellow professor of Luther at the University of Wittenberg, included the Book of Esther in his third and lowest class of biblical books which he termed tertius ordo canonis. Despite what Luther had claimed concerning the Book of Esther, he included it in his translation of the Bible.[58] The low esteem in which Esther was held by prominent Protestant reformers reflects the polarisation of views that were characteristic of the book almost from its beginnings. However, it would be wrong to think the discussion surrounding the virtues of Esther stopped after the Reformation period. We have observed those communities which did and did not include Esther in their canon; more fundamental are the reasons why the Jews and Christians had such a hard time accepting Esther. Brighton summarises the tensions in Jewish and Christian writings,

Jewish opposition to Esther surfaces in at least two areas, the one theological and the other historical. The principal theological objection, according to the Jerusalem Megilla 70d, is that the celebration of Purim stands in conflict with the statute of Leviticus 27:34. This statute suggests that only laws and festivals of the Mosaic code were to be observed by Jews. However, in Judaism this did not always hold true, because Hanukkah was a religious festival accepted by Jews and was not prescribed by Moses. Jewish objection also centered on the absence of any religious elements. While the king of Persia is mentioned several times throughout the book, God is not once mentioned. Especially objectionable was the fact that neither Law nor Covenant is even so much as alluded to, let alone mentioned as having any role in the book—these two concepts run throughout the Old Testament. Probably the best defense of Esther in view of its secular character is that the author intended his story to be a "parody" of paganism, as suggested by Cohen, or a "wisdom tale, a historicized wisdom tale" as Talmon called it. It is a graphic portrayal of "Wisdom motifs" in the characters of Esther and Mordecai and thus should be understood theologically as Wisdom literature. But even if one were to view Esther as "veiled Wisdom Theology," and thus explain the absence of anything religious or theological, it does not help in understanding Esther.

Jewish opposition to the historicity of Esther not only includes the questioning of elements within the story itself—such as Vashti's refusal to obey the king's command (1:12); a feast given by the king lasting 180 days (1:1-3); letters sent out in all the languages of the empire instead of in Aramaic (1:22; 3:12; 8:9), but also and in particular the origin of the feast itself. As the name of the feast suggests, Purim could have been non-Jewish in origin. The secular character of the feast with its excessive drinking and partying in place of religious activities of prayers and sacrifices also suggests a pagan origin. Paul Lagarde hinted at the possibility of its origin in the Persian festival of the dead. Others saw the origin in the Babylonian myths or festivals. Whatever the origin, Jewish or non-Jewish, the festival of Purim in Judaism, as also in the Christian world, has been suspect because of its secular character and possible origins in a non-Jewish pagan setting.[59]

Of course, one does not need to turn to modern theologians for a summary of Jewish tensions. Their feelings are clearly evidenced by the additional narrative expansions introduced by them into the text of Esther more than 2,000 years ago. For the Hellenised Jews in particular, Esther and Purim were well-received.[60]

Christian opposition to the Book of Esther can be said at least to equal that of Judaism. The secular character of the book as well as the obscure origins of the festival of Purim made Esther even more meaningless for Christians. As in the case of Qumran, the Christian church found no counterpart in its calendar for Purim—as it did for the festivals of Passover and Pentecost. If the Jew had difficulty applying or deriving any comfort from Esther, the Christian certainly had more. In fact, at times Christians found the book to be anti-Gentile and too nationalistic to be of value in application. But the greatest difficulty the Christian has had with Esther is that not once is it alluded to in the New Testament. There is no quotation, no reference, and no allusion to the book. As far as the New Testament is concerned, Esther does not exist, for no use whatsoever is made of it. This is not surprising, perhaps, when it is remembered that Esther has no explicit reference to or stated place in the covenant history of God and Israel. What is surprising, however, is that in the entire New Testament there is no reference to or hint of either Esther or the festival of Purim. As in the case of the Dead Sea scrolls and Qumran, it could be said that from such an absence in the New Testament scrolls the Book of Esther and the festival of Purim had no place in the Christian community. Whether this is a possible interpretation (by silence) or not, early Christianity did not comment on the book or the festival, for whatever reason. Furthermore, a Christian commentary on Esther was not written until Rhabanus Maurus' work in 836, and even casual references are rare among the church Fathers. Today, Christians are no further advanced in the use of the book. In Judaism both the book and the festival overcame whatever rabbinical opposition existed, and may still exist, so that as a result both today are popular. But not so within Christianity. While on the one hand we acknowledge its beauty in its story interest, even to the extent of reckoning it "among the masterpieces of world literature," we, nevertheless, still see it as "an uninviting wilderness," theologicaly speaking. Even Christian attempts to theologize the book have failed in gaining the acceptance of it in Christian piety. So, contrary to what has happened in Judaism, Esther for all intents and purposes remains a closed book for Christians. What is the answer?[61]

Brighton’s proposes a kind of intermediate solution. He believes what is presupposed in the Hebrew MT is explicitly stated in the Greek text. Therefore, he recommends reading the Hebrew MT in light of the Greek text in order to “rescue Esther from near oblivion in its usage in the church”. He finishes his conclusion by stating the Greek text should act as a commentary on the Hebrew MT until such time modern Christians attain a level a “theological insight”, at which point the Greek text can be dispensed with in favour of ‘canonical’ Esther (i.e., Hebrew MT version).[62] Brighton touches on an important point and that is the non-usage of Esther in exposition. In his thought provoking essay on the notion of canon and its multiplicity of meanings, Ulrich mentions this phenomenon which is known as “a canon within a canon”. This occurs when some books are given priority over others by virtue of conflicting theologies within the canon,[63] each reader locating their own preferences and religious leanings. Thus although physically part of today’s Christian canon, Esther is very seldom preached from or expounded upon ensuring a reduction in its status to that of opus non gratum.[64]

SHOULD THE BOOK OF ESTHER BE USED AS EVIDENCE AGAINST THE QUR’AN?

Why have such lengthy detailed discussions on the historicity, canonicity and textual stability of Esther? What do the details here have to do with the mention of Haman in the Qur’an? It is clear if one reads the sample of critical comments provided in section three, none of the critics thought it necessary to establish the historicity of Esther and its characters,[65] before claiming the Qur’an contradicted the earlier necessarily historical account of Haman found in the Bible (i.e., in the Book of Esther). Both the historicity and textual stability of the Book of Esther are assumed and then the arguments are made. Since the Book of Esther is not historical, the characters mentioned in the book can in no way be connected with actual Persian history. Therefore, the name “Haman” mentioned in the book is clearly fictitious. Given such problems, the placing of the name “Haman” by the Qur’an in ancient Egypt can’t be considered unhistorical on the basis of a person named Haman in the Book of Esther - for it can suggest that a person with a similar name can also exist in another part of the world and in a different time period - a possibility which many critics refuse to even consider. In any case it seems clear the Book of Esther cannot be used as evidence against the Qur’an, when such evidence is used to unequivocally prove the Qur’an contradicts the earlier, more “reliable” biblical account purportedly confirmed by secular knowledge.

One could argue that even if Esther and its characters have no historical basis, the Qur’an has merely misappropriated a fictional character from an unhistorical setting. Not all scholars predicate their criticisms on the appearance of Haman in the Qur’an in a different historical period than that of Esther, on the basis of the assumed historicity of the later. It is to these criticisms we now turn.

5. Hmn In Context: A Literary And Source Critical Assessment Of Silverstein’s Hmn

Seeking to elucidate the cultural-religious context of the Qur’an, Silverstein’s stance on the controversy of the appearance of a person named Haman in the Qur’an has moved the conversation into unchartered territory.[66] Instead of arguing on the basis of the historicity of Esther and its characters as the majority of earlier critics have done either explicitly or implicitly,[67] he has brought to attention never before used sources, such as the story of Ahiqar and Samak-e Ayyr, in addition to those better known and widely quoted. Silverstein’s textual tour de force is remarkable, as one is taken on a journey in time from the neo-Assyrian Empire all the way down to 14th century Persia, a time span approaching two millennia. After reviewing some medieval Islamic commentators, Silverstein conclusively shows the Haman they were describing was certainly indebted to the corresponding biblical narrative.[68] For this reason he believes any modern attempts to loosen the connection between the two to be unconvincing. Naming A. H. Johns as a notable dissenter in the prevailing Western scholarly consensus, Silverstein says such arguments against the association of the two Haman’s “... forces us to explain systematically Haman’s transition from the Bible to the Qur’an.”[69] After an ordered survey of the literary evidence, Silverstein concludes Qur’anic Haman and Esther’s Haman “have been shown to be one and the same.”[70]

PROBLEMATIC TERMINOLOGY OR SERIOUS METHODOLOGICAL FLAW?

A not inconsiderate number of early commentators of the Qur’an sought to further explain some of the incidents reported there, and resorted to supplementing their knowledge with details from stories they heard from Jewish and Christian informants among others. Showing that medieval commentators used biblical material to explain stories and characters found in the Qur’an is not a new discovery. It was in this very milieux that these medieval Muslim scholars applied a technical term to such sources, naming them isr’liyyt.[71] Usually the term isr’liyyt was applied to stories of Jewish origin, though more generally it could also be applied to any information whose origin was not to be found in the Islamic historical tradition; it was also used to designate a corpus of reports deemed unreliable for use. The material usage of such sources in Qur’anic exegesis has been critically discussed conceptually in Islamic circles approaching 1,000 years. Though he did not use the term isr’liyyt, the Andalusian exegete Ibn Atiyya (d. 541 AH / 1146 CE) was the first scholar to pay systematic attention to the implausibility of these types of reports, more than two centuries before the critical exegesis of Ibn Kathr's (d. 774 AH / 1373 CE).[72] With this in mind, Silverstein’s defence of the isr’liyyt stories regarding Pharaoh and Haman transmitted by some medieval commentaries is puzzling; he seems to be suggesting only those Islamic accounts based on biblical material are convincing. Indeed, instead of focussing on Haman and Pharaoh as found in the Qur’an and the Qur’an alone, Silverstein uses these obviously derivative accounts to prove the Qur’an is derivative, and it is the backbone of his methodology. Once realised, it is easy to spot the flaw in the process: derivative writings on a text do not imply the text itself is derivative. One (out of many) of the best examples of this inconsistent methodology is the sub-section ‘Genealogical relationship between the book of Esther’s Haman and the Qur’anic Pharaoh’.[73] He states the preceding characters were widely acknowledged as having been “blood relatives”.[74] Crucially, the reason for this link is based on Qur’an commentaries and not the Qur’an. Nowhere does the Qur’an give any concrete information as to Pharaoh’s ethnic origin, let alone that he was Amalekite or Persian. In fact, the Qur’an gives none of the information used by Silverstein to show Esther’s Haman and the Qur’anic Pharaoh were “blood relatives”. Utilising the commentaries of al-Tabar, al-Maqdis and al-Qurtub whom themselves, are, in places, strongly indebted to their biblical forerunners, to then claim this is what the Qur’an itself promotes is a mischaracterisation of the evidence at the least, or a misrepresentation of the evidence at the worst. Perhaps Silverstein recognised this problem of terminology himself as the concluding sentence of the sub-section uses the term ‘Islamic’ instead of ‘Qur’anic’ as found in the subtitle. Going to an even further extreme, evidence of Qur’anic commentaries can be relevant even when they contradict what the Qur’an itself says! What relevance can such a statement have when it is in open opposition to what is mentioned in the Qur’an? Silverstein says it is ‘noteworthy’ some Qur’anic commentators believed the Pharaoh of Joseph’s time was the same Pharaoh of Moses.[75] But the Qur’an never mentions any character called ‘Pharaoh’ in Joseph’s time, rather the ruler is consistently called as ‘King’. The evidence of some commentators may be ‘noteworthy’ in the sense they support Silverstein’s reading, but if one is interested in what the Qur’an has to say for itself, the significance is lost.

Thus a major methodological problem of Silverstein’s literary analysis is equating Qur’anic commentaries that appear centuries later in a much changed religio-cultural geo-political milieu, in meaning with the Qur’an itself. This problematic method underwrites a significant portion of Silverstein’s literary comparisons, rendering its conclusions void, if what is meant by the use of terms such as ‘Qur’anic’ is the Qur’an alone and not later writings on the Qur’an. One is free to describe words in their own terms, but words have meanings and these meanings are conveyed to the reader. If ‘Qur’anic’ has a wider textual application than its straightforward contextual interpretation would suggest, this should be explained to the reader. One may justifiably ask what the following summarised phrases in his article mean, ‘Qur’an(ic) Haman’, ‘Haman who makes a transition to the Qur’an’, ‘Haman who appears in the Qur’an’, ‘Qur’anic figure of Haman’ , ‘Haman depicted in the Qur’an” and “two Haman’s’? Do they mean Haman as found exclusively in the Qur’an, or do they mean Haman as found primarily in Qur’anic commentaries, or a mixture of the two? The same could also be said of Qur’anic Pharaoh. Weighing these objections together, the failure to maintain an accurate distance between the different contexts in which these characters appear, is a terminological problem bordering on a serious methodological flaw. Instead, sometimes we are left to wonder just which Haman (i.e., Qur’an or Qur’anic commentaries) Silverstein thinks has been appropriated from biblical literature. In many cases it is clear he is mainly concerned with the Haman as supplemented by the Qur’anic commentaries, which as we have already said, he has conclusively shown to be indebted to its biblical counterpart. Nevertheless, when these later writings are interrogated and found to contain material of obvious biblical origin, their context cannot be back projected into the Qur’an.

Despite these problems, a number of intriguing new sources are brought into the discussion which cannot be ignored. These sources are rarely used in terms of their application to the Qur’anic text, not in the sense of their actual discovery, and it is to Silverstein we owe their initial application to the Qur’anic account of Haman. In what follows we discuss the evidence adduced by Silverstein purporting to show Qur’anic Haman is based on biblical Haman, only when it is clear he is talking about Haman of the Qur’an and not the Qur’anic commentaries. To maintain congruity, we proceed along roughly the same outline given in his article, diverging where necessary for appropriate discussion.

BIBLICAL HAMAN AND QUR’ANIC HAMAN: SIMILARITIES, DIFFERENCES OR BOTH?

Silverstein says,

There are three significant differences between the Biblical and Qur’nic Hamans; to demonstrate that the latter is based on the former, these differences must be accounted for. The first is that the Qur’nic Haman is Pharaoh's helper whereas in the Bible Pharaoh has no helpers. The second is that the two Hamans appear in completely different historical contexts: Achaemenid Persia is more than a thousand miles and years away from Pharaonic Egypt. The third is that whereas the Biblical Haman is integral to the story of Mordecai and Esther at Ahasuerus's court, the Qur’anic Haman is completely divorced from the Book of Esther context and no other figures from the Book of Esther appear in the Qur’n.[76]

The first of Silverstein’s proposed obstacles turns out on closer inspection to be ineligible and, therefore, not a difference that needs to be accounted for. He says, “The first difference is the easiest to settle: although a comparison between the biblical and Qur’nic Pharaohs indicates that only in the Qur’n is Pharaoh supported by helpers, ...”[77]

This is incorrect. The biblical Pharaoh is supported by counsellors as a cursory reading of the book of Exodus would confirm. Perhaps Silverstein meant to say that Pharaoh did have ‘helpers’ but that they were not named in the Bible and since the Qur’an names a ‘helper’, i.e., Haman, one must therefore look to see at what point in history the biblical Pharaoh was assigned named ‘helpers’. Weighing against this possibility is the next part of his sentence, “... already in Late Antique monotheistic circles the biblical Pharaoh was widely believed to have had henchmen.”, which indicates that it is the mere presence of ‘henchmen’ that is significant and not the fact that they were named. Thus he is able to find an invented ‘missing link’, and, resultantly, sees the appearance of Haman as Pharaoh’s ‘helper’ in the Qur’an through the following three stage process:

Pharaoh had no helpers in the Bible.

Already in late-antique monotheistic circles biblical Pharaoh is given ‘henchmen’.

The Qur’anic account of Pharaoh’s helper (i.e., Haman) emerges from the biblical account via the aforementioned step.

We have already shown the first stage is wrong. Oddly enough, the reference cited by Silverstein states Pharaoh did have helpers! Kugel calls them “close advisers”[78] and goes on to say, “Now, it is noteworthy that in the biblical account, the unnamed counsellors or wizards of Pharaoh do more than merely give advice...”.[79] What Kugel does is that he gives a list of references to the names of biblical Pharaoh’s advisers as they appeared in texts dating from antiquity onward.[80] Silverstein has misjudged the nature of the biblical evidence and confuses the matter by connecting the Qur’anic account to the biblical narrative via late antique texts that are unnecessary. Furthermore, it should also be noted that none of these named helpers given by Kugel as cited by Silverstein are called Haman or derived from Haman. If the Qur’anic account emerged in this context as is confidently stated, then why do none of the five names mentioned, Jannes, Jambres, Balaam, Job and Jethro appear in the Qur’anic narrative? Though it may seem one is assisting Silverstein by reducing the number of differences required to make a connection, the unnecessary inclusion of supposed differences that are quickly and easily accounted for can give a misleading impression.

THE RULER OF ANCIENT EGYPT IN THE QUR’ANIC STORY OF JOSEPH AND MOSES

The first real difference to which we now turn our attention (i.e., Silverstein’s second difference) is the completely different historical context of biblical Haman and Qur’anic Haman. The Qur’anic account places the narrative in Pharaonic Egypt while the biblical account places the narrative in Achaemenid Persia – more or less 1,000 miles and years away. Silverstein adopts a two-step approach to resolve these obstacles. In reverse, the second step aims to show that there was a genealogical relationship between Esther’s Haman and the Qur’anic Pharaoh. We have already discussed the second step earlier and have shown the analysis there has no foundation in the actual Qur’anic narrative.

Step one aims to show there was a literary relationship between the Book of Esther and biblical descriptions of Pharaoh’s court – a point which is very capably demonstrated. The courts of Ahasuerus and Pharaoh were associated beginning from the time the author of the Book of Esther penned his work and to subsequent generations of Jews all the way to modern biblical scholars.[81] The Pharaonic episode Silverstein says influenced the author of the Book of Esther was the story of Joseph, providing numerous examples in the process. Additionally, he informs the reader this is also the conclusion adopted by modern biblical scholars. However, the Haman of the Qur’an is not associated with the Egyptian court of Joseph, a story that is narrated in srah Ysuf, rather it is the Egyptian court of Moses to which he is associated. Silverstein immediately recognises this problem but relegates the discussion to a footnote![82] To counter the evidence provided in the Qur’an, he turns to Qur’anic commentaries and shows at least one commentator believed the Pharaoh at the time of Joseph and Moses in the Qur’an was actually one and the same person – a statement he considers ‘noteworthy’. But the Qur’an never mentions any character called Pharaoh in Joseph’s time, rather the Egyptian ruler is consistently referred to as ‘King’. A contextual reading of the episodes of Joseph and Moses narrated in the Qur’an unequivocally shows we are dealing with two different historical periods. There are no details which connect one narrative to the other. The evidence of some commentators may be ‘noteworthy’ in the sense they support Silverstein’s reading, but if one is interested in what the Qur’an has to say for itself, the significance is lost.

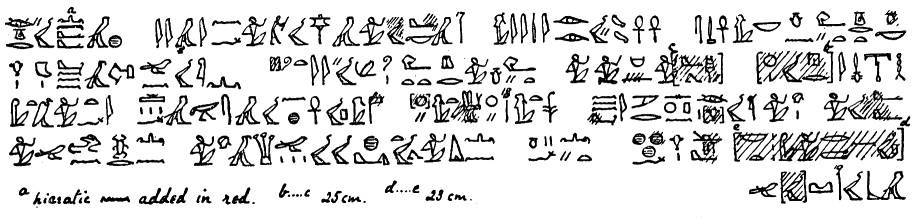

Furthermore, we believe there is significance in the way which the Qur’an refers to the Egyptian ruler in Joseph and Moses time, ‘King’ and ‘Pharaoh’, respectively, something not considered by Silverstein. The rulers of ancient Egypt during the time of Abraham, Joseph and Moses are constantly addressed with the title ‘Pharaoh’ in the Bible. The Qur’an, however, differs from the Bible: the sovereign of Egypt who was a contemporary of Joseph is named ‘King’ (Arabic, malik); whereas the Bible has named him ‘Pharaoh’. As for the king who ruled during the time of Moses the Qur’an repeatedly calls him ‘Pharaoh’ (Arabic, firawn). According to modern linguist research the word ‘Pharaoh’ comes from the Egyptian per-aa, meaning the ‘Great House’ and originally referred to the palace rather than the king himself. The word was used by the writers of the Old Testament and has since become a widely adopted title for all the kings of Egypt. However, the Egyptians did not call their ruler ‘Pharaoh’ until the 18th Dynasty (c. 1552–1295 BC) in the New Kingdom Period. In the language of the hieroglyphs, ‘Pharaoh’ was first used to refer to the king during the reign of Amenhophis IV (c. 1352–1338 BC). We know that such a designation was correct in the time of Moses but the use of the word Pharaoh in the story of Joseph is anachronistic, as under the rule of the Hyksos, the period to which he is usually ascribed, there was no ‘Pharaoh’.[83]

There cannot really be much doubt that a literary relationship exists between the Book of Esther and biblical descriptions of Pharaoh’s court, and that such a relationship was held by Jews from the time the author of Esther penned his work, until the eve of Islam and after Islam. The real question is whether the Qur’an has appropriated this context for its own narrative design. The Pharaonic episode believed to have influenced the Esther narrative is that of Joseph’s career. Significantly, the Qur’an does not assume this context or any of its details, but rather places Haman in the Pharaonic court that existed during the time of Moses.

QARN (KORAH) IN THE QUR’AN, BIBLE AND MIDRASH: WHO BORROWED FROM WHO?

Korah, son of Izhar, appears in the Bible in the narrative concerning Moses [Numbers 16:1-50] and the same character also appears in the Qur’an. Qarun is mentioned by name four times [Qur’an 28:76, 79; 29:39; 40:24] and is described as being from the people of Moses [Qur’an 28:76] and of great wealth and status [Qur’an 28:76,79]. Moses showed Qarun miraculous signs given to him by God, but was instead rejected as a sorcerer and liar [Qur’an 40:24]. Described as an arrogant sinner, Qarn was punished by death for his sins and unjust behaviour [Qur’an 29:39-40].

As there is another character named Korah in the Bible who had a half-brother who had a son called ‘Amaleq [Genesis 36:15-16], Silverstein discovers an ulterior motive in the Qur’anic mention of Qarun and believes it may have conflated the two Korah’s as it has already grouped the Amalekites Pharaoh and Haman together.[84] For want of sounding like a broken record, we repeat once again: nowhere in the Qur’an is the ethnicity of Haman or Pharaoh given, let alone they were Amalekites or Persians. The argument here simply does not follow. But there is a more amusing point to be taken from this line of thought. According to Silverstein, Muhammad or whoever else he thinks (co)authored the Qur’an, is more than capable of delving into intricate biblical genealogies picking out a half-brother’s son and assigning him some special significance, whilst at the same time forgetting to check another character he appropriated (i.e., Haman) was 1,000 years and miles out of place.

For Arthur Jeffrey, the mere fact that Haman was mentioned alongside Korah in rabbinic legends was reason enough for one to believe the Qur’anic Haman was derived from biblical Haman.[85] This kind of one-dimensional approach may have been suitable when he penned his views in the late 1930’s, but much textual and methodological progress has been made since then, and we now have a much better understanding of the chronology of Jewish, Christian and Muslim literature. The study of Midrashic literature including its chronology is an on-going process still being undertaken today.[86] In many cases where critics believe the Qur’an has copied ‘earlier’ Jewish sources, especially rabbinic texts, it may very well be the other way around.[87] Silverstein also sees significance in the citation of Esther’s Haman and Korah in Jewish Midrashic accounts though he is more restrained than Jeffrey in drawing specific conclusions in relation to the Qur’anic narrative. Providing a quotation from Pirqe de Rabbi Eliezer that mentions Korah and Haman in the same sentence, Silverstein finds ‘links’ between Esther’s Haman and Korah,[88] no doubt seeking to draw from this the antecedents of the Qur’anic narrative. What is insinuated by the term ‘links’? If Silverstein is suggesting as previous scholars before him have, that this quotation provides evidence the Qur’an understood Korah and Haman to be contemporaries, then this is rejected by a close reading of the passage (Silverstein gives only a partial rendering) in its surrounding context (i.e., reading on an extra few sentences). Though Haman is mentioned alongside Korah, the author of the passage makes it clear they belong to different nations of the world and are obviously not considered contemporaries.[89] On the basis of this excerpt, it is simply not possible for one reading or hearing this excerpt to conclude these two characters were contemporaries in Egypt.

But there is something more fundamental that demands attention. Believing the Qur’anic narrative of Haman to have a history, Silverstein does not seem to think it worthwhile to inform the reader the sources he utilises also have a history. Surely, this is a matter of importance given the nature of his enquiry? For example, the excerpt “linking” Korah and Haman is firmly dated to the 4th century CE. There is no mention at all that the source it is taken from (i.e., Pirqe de Rabbi Eliezer) received its last redaction well into the Islamic period, exists in numerous manuscripts that differ from each other none of which pre-date the 11th century, and is not quoted but any other Jewish writer before the 9th century.[90] This problem occurs elsewhere with other texts also.

Moving on, we are introduced to the poet Shhn of Shrz. The conclusion drawn from this text suggests that Korah had a place in the Esther story “at least to the Jews of medieval Persia”.[91] Though it may help identifying later medieval views of Korah and the Esther story, what relevance the text of a 14th century Judaeo-Persian poet has for one attempting to establish the derivation of Qur’anic Haman from biblical Haman is anybody’s guess.

ÊÍãóøáÊõ æÍÏíó ãÜÇ áÇ ÃõØíÜÞú ãä ÇáÅÛÊÑÇÈö æåóÜãöø ÇáØÑíÜÞú

Çááåã Çäí ÇÓÇáß Ýí åÐå ÇáÓÇÚÉ Çä ßÇäÊ ÌæáíÇä Ýí ÓÑæÑ ÝÒÏåÇ Ýí ÓÑæÑåÇ æãä äÚíãß ÚáíåÇ . æÇä ßÇäÊ ÌæáíÇä Ýí ÚÐÇÈ ÝäÌåÇ ãä ÚÐÇÈß æÇäÊ ÇáÛäí ÇáÍãíÏ ÈÑÍãÊß íÇ ÇÑÍã ÇáÑÇÍãíä

-

FROM TOWER TO TOWER: THE STORY OF AHIQAR AND PHARAOH’S SARH

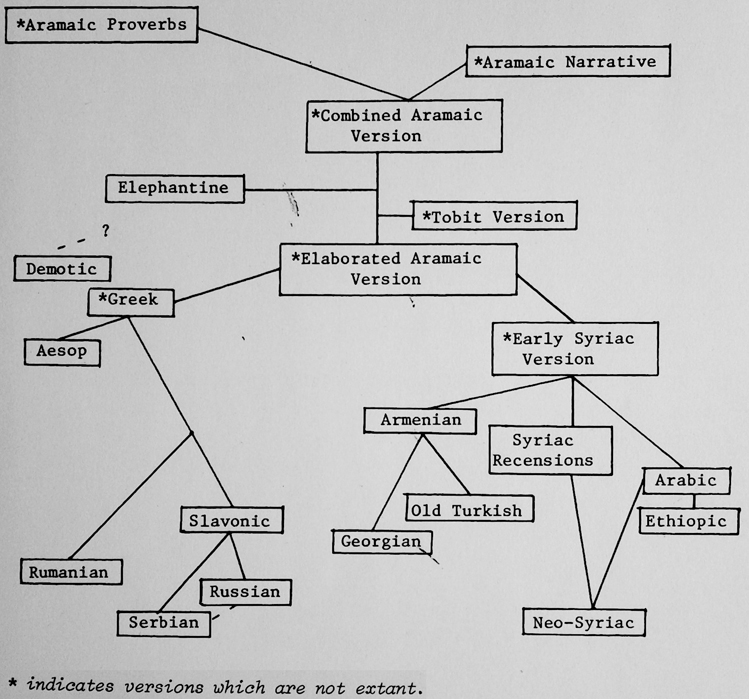

Based on biblical information, many Qur’anic exegetes believed the ‘lofty tower’ (Arabic, sarh) ordered to be constructed by Pharaoh was the Tower of Babel. Once again, this statement has no basis whatsoever in the Qur’an and there is not a shred of internal evidence to link Pharaoh’s sarh to the Tower of Babel. Silverstein realises this is the case[92] and instead of recycling old arguments, he makes a genuinely innovative manoeuvre and asserts the story of Ahiqar is ultimately responsible for the Qur’anic Pharaoh passing his orders on to Haman. So what is the story of Ahiqar? A piece of ancient near eastern wisdom literature, Ahiqar is a work of two parts; the first part contains the narrative, the second part contains the wisdom of Ahiqar and gives a list of over a hundred of his sayings, many of which are difficult to understand. Lindenberger provides a basic summary of the narrative,

Ahiqar is an advisor and cabinet minister of Sennacherib, king of Assyria (704-681 B.C.). This Ahiqar, while still a youth, had been warned by astrologers that he would have no children. When he reaches adulthood, the prophecy comes true, in spite of prodigious efforts on his part to thwart it, including the marriage of sixty wives! Eventually he appeals for divine help, and receives an oracle instructing him to adopt his nephew Nadin (or Nadan, in some versions) and raise him as his son. Ahiqar is to instruct Nadin in all his wise lore so that when the boy reaches the age of majority, he will be a fit successor. The king gives his approval, and Ahiqar proceeds to instruct his adopted son.

At this point in most versions of the narrative, there comes a long series of proverbs and aphorisms purporting to be what Ahiqar taught Nadin. When the narrative resumes, Ahiqar has become an old man. Nadin has forsaken the admonitions of his aged guardian and has set his hand to plotting against him. The young man forges letters in Ahiqar’s name, and contrives to convince the king that his elderly advisor has committed treason against the crown. Sennacherib is furious at having been betrayed, and gives peremptory orders that Ahiqar should be put to death.

By coincidence it happens that the officer detailed to carry out the execution is a man whose life Ahiqar had saved under similar circumstances many years earlier. Ahiqar recognises him, and urges him to reciprocate the gesture. The two agree to kill a slave and pass his body off to the king as that of Ahiqar, while the officer preserves the sage and his wife – there now appears to be only one – in a secret underground hiding place.

Not long afterwards, Sennacherib receives a letter from the king of Egypt, offering him the entire revenue of Egypt for three years if he can send him an architect skilled enough to help build a castle between earth and heaven. The Assyrian king is greatly distressed, because he knows that of all wise in his realm, only Ahiqar possessed such knowledge. Sennacherib’s officer perceives that the time is ripe, and comes forward fearfully to confess that he did no carry out the royal death warrant, that Ahiqar is alive and well. The king weeps for joy and immediately sends for Ahiqar, delegating him to go to Egypt to carry out Pharaoh’s demands.

Ahiqar quickly recovers from his ordeal, and goes to Egypt, where he astounds the court by a series of impossible feats demonstrating his superior wisdom. Three years later Ahiqar returns to Assyria, bringing the promised revenue. Pressed by a grateful Sennacherib to accept a reward, Ahiqar declines, asking only that he be allowed to discipline the ungrateful Nadin as he please. With the king’s approval, he has Nadin imprisoned and severely tortured, after which Ahiqar addresses him with a long series of reproaches. (A typical example is, “My son, thou hast been like the man who saw his companion shivering from cold, and took a pitcher of water and threw it over him.”) Thereupon Nadin “swelled up like a bag and died,” bringing the story to its end.[93]

Armed with a summary of the narrative, what themes are discernible? What social and religious message, if any, does the story of Ahiqar impart? Lindenberger and others consider Ahiqar to be a non-Jewish text, a folktale of a wise counsellor, with the narrative section showing the presence of some basic themes, such as the downfall and restoration of a just vizier, and the betrayal of a powerful person by an ungrateful relative – well documented and widely known folk-motifs. Theologically speaking, the narrative says nothing directly about God, a topic widely encountered in the proverbs section – though it is the Gods of Aram, Canaan and Mesopotamia which are encountered and not the God of Israel.[94]

Other scholars, who consider Ahiqar a Jewish text, interpret the narrative differently. Viewed as part of a group of Jewish texts composed between the 8th century BCE and mid-2nd century BCE, Chyutin believes the story of Ahiqar, like the other texts he analyses, addresses the major problems of the Jewish populations, whether in the ‘Land of Israel’ or the ‘dispersions’. Thus, based on an acceptance of the story as a Jewish text (the Jewish characters being Ahiqar and Ndin), generally speaking, it deals with the meaning of life after the Babylonian exile and how Jews were integrated into a new country, accepting this diaspora as a natural way of life, not seeking to change it. The royal court is depicted as a place where there are no ethnic prejudices, concerned only with the desire for good governance. Contrary to Esther, preaching the breaking of national and familial solidarity, Ahiqar advocates the removal of former racial and ethnic boundaries and integration into Assyrian society to the point of assimilation.[95]

One will observe from the outset, in its outline, no narrative even remotely similar to this is recounted, mentioned or hinted at anywhere in the Qur’an. No literal parallels exist, which makes the claimed correspondence between both texts all the more interesting. Silverstein’s argument can be summarised as follows:[96]