-

FOR EVERY STORY, A VILLAIN NAMED HAMAN

Silverstein argues the Book of Tobit and other evidence suggests Haman should be viewed as an ahistorical figure in pre-Islamic times, a ‘bad guy’ who could dip in and out of literary contexts as desired.[117] We have already shown that the name Aman is spelt this way only in certain versions of Tobit, and in just one verse 14:10, which some scholars have read into the personage of Haman. It could just as easily be a scribal error with no theological overtones, as the large number of other ‘corrupted’ spellings recorded in the manuscripts suggests. Recent analysis of this verse and its intertextual parallels suggests it is the Psalms that play a primary role in understanding this verse and not the Book of Esther and its characters. Silverstein seeks to develop his idea – Haman existing as a topos in near eastern literatures – by looking at the post-Islamic usage of Haman. This, of course, could not have served as the basis for the Qur’anic depiction of Haman and so we move on to the alleged pre-Islamic evidence. Along with the Babylonian Talmud, the first Targum to the Book of Esther is mentioned as constituting the pre-Islamic evidence. Modern scholarship dates the Targums of Esther to the 7th – 8th century at the earliest so this document cannot be conclusively dated to pre-Islamic times and is very likely post-Islamic.[118] In terms of documentary sources, one of the earliest if not the earliest extant manuscript for any Targum of Esther was found in the Cambridge Genizah collection (from Cairo Genizah) and is dated to the 10-11th century CE.[119] We are not seeking to deny the Book of Esther’s Haman existed as a topos in early Jewish literature pre-dating Islam, which may or may not be the case. The problem arises as this whole line of thought is predicated on and consequently developed based on the assumption that Qur’anic Haman is derived from biblical Haman which, on the basis of the evidence presented, we have shown not to be the case. Methodologically speaking, it is thus not a truly independent way of interpreting the evidence.

Navigating our way past the 14th century Judaeo-Persian poet who pops up yet again, it is necessary to comment on a curious piece of evidence admitted by Silverstein, a Persian popular romance named Samak-e Ayyr. So sure is he of the text, it forms an integral part of his overall conclusion where he states the text took part in the evolution of Haman from the Bible to the Qur’an.[120] There are some major, one might say insurmountable difficulties with this assessment. Based on internal evidence scholars suggest the text was written down in the 12th century CE. Gaillard thinks the origin of the story may go back to a period earlier than when it was written down but does not commit herself.[121] There is a solitary manuscript attesting the text which is dated to the 14th century CE and is kept in the Bodleian Library.[122] To claim a Persian romance believed to have been written down in the 12th century, whose origins might be based on earlier oral sources, and preserved in a single manuscript from the 14th century, took part in the evolution of Haman from the Bible (Esther c. 4th cent BCE – 3rd cent BCE) to the Qur’an (c. 610-632 CE), simply for mentioning a villain named Haman, seems to exceed chronological acceptability. Which parts of this text date at or around the time of the composition of the Qur’an? What evidence is there to suggest so? What evidence is there to suggest this story circulated in north west Arabia around the time of Muhammad? How was this text acquired, in what form, from whom and from where? Unfortunately these questions are never posed, so one can only speculate as to the answers. In any case, should one maintain this text, or part of this text, was one of the sources of the Qur’an, further more detailed examples need to be submitted for proper evaluation.

6. Parallelomania

In his Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis in 1961, the New Testament Jewish scholar Samuel Sandmel lectured on the dangers of parallelomania. As was usual practice, his address was published the following year as the first article in the society’s journal and it would later become a seminal essay.[123] He defined parallelomania as,

that extravagance among scholars which first overdoes the supposed similarity in passages and then proceeds to describe source and derivation as if implying literary connection flowing in an inevitable or predetermined direction.[124]

Sandmel was of course writing about the Old and New Testament but his instructive observations are not limited to this sphere of literature. Highlighting the issue of abstraction and the specific he says,

The issue for the student is not the abstraction but the specific. Detailed study is the criterion, and the detailed study ought to respect the context and not be limited to juxtaposing mere excerpts. Two passages may sound the same in splendid isolation from their context, but when seen in context reflect difference rather than similarity. The neophytes and the unwary often rush in,...[125]

And it is in this observation we may identify a fault in Silverstein’s method. He has isolated six verses containing the name Haman and deprives them of their context in the larger narrative. No efforts are made to integrate the Qur’anic Haman into his larger context in the Moses-Pharaoh narrative, and how this narrative relates to the srah in which it is found and to the rest of the Qur’anic message. We are even short by the way of excerpts let alone that they are analysed in isolation from their context. The only literary excerpt from the Qur’anic text ever introduced is Pharaoh commanding Haman to build a ‘lofty tower’. This is the case with almost every critic who has written on this issue that we are aware of. Admittedly, Haman is mentioned only a few times in the Qur’an, but this makes it all the more important for one to search through the context in which he is mentioned relating the parts to the whole, before engaging in a juxtaposition of excerpts and deriving literary dependence. There are no extended thematic or literal parallels, instead the basis of the argument is a catchword, i.e., Haman, and a loose literary parallel, the construction of an edifice between heaven and earth. Focussing on the similarities and forgetting about the differences, it is rarely mentioned when there are instances where parallels don’t exist, or where there are direct contradictions. In a couple of instances where problems are mentioned, they are consigned to footnotes and are not given suitable prominence. The vaguest of parallels are clung too, whist obvious inconsistencies are ignored. More problematic than this are instances when parallels are read back into the Qur’an from later literature when the Qur’an gives no basis for such a claim. An obvious example is Qur’anic Pharaoh being Persian or Amalekite.

Fortunately, when viewed as part of a larger story framework, the specific narrative section containing the construction of an edifice between heaven and earth found in the story of Ahiqar (read. Syriac version chapters 5-7), does indeed lend itself to a typological study, especially those employed by folklorists, following a predictable literary type well known to specialists in folklore studies. According to the classification system originally developed by Antti Aarne (1910), then expanded by Stith Thompson (1961) and later thoroughly overhauled by Hans-Jrg Uther (2004),[126] the core section of the story of Ahiqar accords with tale type 922A, simply known as ‘Achiqar’[127] – a minor variation of tale type 922, ‘The Shepherd Substituting for the Clergyman Answers the King’s Questions (The King and the Abbot)’.[128] Uther describes tale type 922A as follows,

A childless minister adopts his nephew (Achiqar), rears and teaches him. He presents his foster-son to the king, who likes the boy’s clever answers. When the minister becomes old, he recommends the king his foster-son as his successor. The young boy is appointed to the office, but slanders his foster-father. The king orders that the old minister to be killed. Instead, he is saved, and a slave is killed in his place.

When a hostile king learns about the minister’s death, he sets the king tasks that cannot be accomplished by anyone. He asks for a person who is able to build a castle in the air and who can answer difficult questions.

The king searches desperately for his old minister. When he learns that he is still alive, he just reinstates him in his former position. Under a different name the old minister travels to the hostile king. He lets a child sitting in a basket be carried into the air by an eagle, where the boy exclaims, “Give me stones and lime so that I can start building the palace!” After solving all the riddles set by the king, he returns with a rich reward. He asks his foster-son to be summoned and punishes him with a cruel death.[129]

Though categorised as tale type 922A by Aarne-Thompson-Uther, Niditch and Doran have shown there is no problem describing the story of Ahiqar 5-7:23, the thematic core of the work, as tale type 922[130] providing a detailed outline,

Numbers 1-4 list major plot events which move the story from its initial problem to the solution and subsequent reward of the hero. Each of these major happenings is composed of a combination of motifs of action, character, setting, and so on. The primary action motif will be highlighted, within each of the four basic divisions. We should note, however, that certain variations on the motifs are allowed within these major steps. Specific variations on the basic motif, the nuances, will be indicated in the outline of each narrative.

(1) A person of lower status (a prisoner, foreigner, debtor, servant, youngest son are all possible nuances) IS CALLED BEFORE a person of higher status (often a king or bishop or chief of some kind) TO ANSWER difficult questions or to solve a problem requiring insight. (The problem may be posed on purpose to perplex or may be a genuine dilemma. Often a threat of punishment exists for failure to answer.)

(2) The person of high status POSES the problem which no one seems capable of solving.

(3) The person of lower status (who may in fact be a disguised substitute for the person expected by the questioner) DOES SOLVE the problem.

(4) The person of lower status IS REWARDED for answering (by being given half the kingdom, the daughter of the king, special clothing, a signet ring, or some other sign of a raise in status).[131]

If detailed study that respects the context is the criterion as opposed to the juxtaposition of mere excerpts, the detailed outlined given above becomes a crucial piece of evidence providing a basis for the comparison of the entire literary outline of this narrative sub-section. One will immediately note this outline is not applicable to the Qur’anic narrative of Moses and Pharaoh, and therefore, is certainly not applicable to the narrative sub-section dealing with the construction of the edifice between heaven and earth. Even though it can be readily shown in its present state the application of orientalist-folklorist criticism to the Qur’an has not provided any meaningful results,[132] and, that such tale types lack universality, one can usefully proceed on the basis of the structural elements of the story of Ahiqar and the arrangement of its motifs. After giving a detailed outline of tale type 922, Niditch and Doran proceed to explain how the core narrative of the story of Ahiqar neatly fits this typology,

(1) A person of lower status, Ahiqar, the symbolically dead counsellor who has dwelt beneath the earth IS CALLED BEFORE a person of higher status, Sennacherib, king of Babylon (5:11) to solve a problem which is impossible. He must build a castle in the air (5:2) or pay three years' revenue to Egypt (5:3), and neither Nadan nor any of the members of court can solve the problem (5:5, 6).

(2) Person of higher status, Sennacherib, ENUMERATES the problem, castle-building, to person of lower status, Ahiqar (6:1).

(3) Person of lower status, Ahiqar, CAN ANSWER (6:2). (NOTE: 6:2-7:20 contains a repetition of the question and answer motifs, numbers 2 and 3 in the outline.)

(4) Person of lower status, Ahiqar, IS REWARDED, set at the head of the king's household (7:23).

Thus on the formal level - structure of content elements - Ahiqar does share the pattern of type 922. As in other tales of this type, Ahiqar includes a series of trick questions and clever replies. In Ahiqar this process of repeated asking and answering is particularly extended since the wise man must not only deal with his own monarch but must also travel to Egypt to answer Pharaoh's questions in person. It is at Pharaoh's court that the long dialogues take place. The castle-riddle is one among many. The confrontation at Pharaoh's court need not have taken place for the tale to be complete from a typological point of view. Ahiqar could have simply told Sennacherib the details of his plan, the problem would have been solved, and Sennacherib could have rewarded his hero. Yet the story would have suffered stylistically, both from the point of view of the teller and that of the listener. Repetitions in action lengthen the story, intensify the listener's interest, and create thematic emphasis. Here the emphasis is on the cleverness of the wise man who can answer any question which he faces. Such repetitions are typical of and essential to traditional tales.'[133]

Now that we have a much clearer picture of the context and literary structure of the story of Ahiqar, one will observe Silverstein’s linking of the tower in the story of Ahiqar and the tower commanded to be built by Pharaoh, have no literary connection or comparative basis. The explanation given behind the construction of each tower, their purpose and their placement in their respective narratives, shows they cannot be connected to each other in a literary sense. Even given the same typology, similarity in structural outline and/or thematic progression, this does not necessarily imply knowledge of a specific source or text. Moving away from the typological studies employed by folklorists, for example, the invocation-worship-petition sequence of the srah al-Ftihah and its thematic progression can be paralleled with the ‘Lord’s prayer’, and going even further back into ancient near eastern times, the Babylon Prayer to the God Sin.[134] One cannot, of course, then presume the srah al-Ftihah is based, derived, copied or has picked out certain elements, written or oral, from a prayer circulating more than a millennia earlier in Mesopotamia. The context ought to be respected.

Then there is the excessive usage of Qur’anic commentaries and a large number of other sources that clearly post-date the Qur’an. What relevance can such sources have in attempting to prove the evolution of Haman from the Bible (Esther c. 4th cent BCE – 3rd cent BCE) to the Qur’an (c. 610-632 CE)? It is a chronological impossibility. Silverstein is attempting to build up an overall picture of Haman and his alleged transition and so rightly looks to evidence that occurs after the Qur’an to establish a more rounded picture. One needs to be wary though: it is the context before the Qur’an that is more important in determining what the Qur’an allegedly did or did not appropriate, not context occurring afterward, and in some cases up to seven centuries later. With such a heavy emphasis on context after the Qur’an, one is in danger of preconditioning the interpretation of the earlier evidence.

Moving beyond ‘juxtaposing mere excerpts’ raises further methodological questions. Silverstein’s command of the sources is obvious as he moves with ease from the neo-Assyrian empire to 14th century Persia. It may legitimately be asked if there exist even older sources which may also provide parallels to the Qur’anic account. Should it not strike one as anomalous, that at no time are any sources from ancient Egypt discussed, when this is the setting the Qur’an places the character Haman in? This boils down to a question of presuppositions and biases which are not beliefs that we need to hide from view.[135] Silverstein has already decided the Qur’an cannot be describing a real event and deems it unworthy to look back in time any further than the sources he requires to establish his version of events require. Of course, we all have pre-suppositions from where we formulate our arguments but this should not necessarily prevent us from dealing with other evidence. For instance, are the stories of Ahiqar and the Tower of Babel the only two parallel explanations open to us in interpreting the Qur’anic account where the Egyptian Pharaoh asks Haman to build a lofty tower between heaven and earth? These parallels can be found in ancient Egypt and other ancient cultures and is not something unique to those sources.

7. Qur’anic Hmn & Pharaoh In The Context Of Ancient Egypt

Is there any information in the Qur’anic narrative of Pharaoh and Haman that would contradict its placement in an ancient Egyptological context? Fortunately, there are a few cases where the Qur’an ascribes certain beliefs and actions to Pharaoh which at least allow us to check if they are consistent with modern critical investigations into ancient Egyptian history. The following enquiry is limited to information from five verses in the Qur’an, dealing with religious concepts and construction technology.

Pharaoh said: "O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself." [Qur'an 28:38]

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means - The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!" [Qur'an 40:36-37]

The Qur’anic verses concerning Pharaoh and Haman provide us with the following information:

The Pharaoh as god

The making of burnt bricks in ancient Egypt

The desire of the Pharaoh to ascend to the sky to speak to gods

Pharaoh had a leading supporter called Haman

Let us now investigate these statements in the light of Egyptology and primary source evidence. The Bible does not provide any information regarding the above mentioned statements in an ancient Egyptian setting; nor, as far as we are aware, is it explicitly stated in any secular literature from the time of Muhammad.

THE PHARAOH AS GOD

For all kings, the Bible uses the term “Pharaoh” to address the rulers of Egypt. The Qur’an, however, differs from the Bible: the sovereign of Egypt who was a contemporary of Joseph is called the “King” (Arabic, malik); he is never once addressed as Pharaoh. As for the king who ruled during the time of Moses, the Qur’an repeatedly calls him “Pharaoh” (Arabic, firawn). These differences in detail between the biblical and Qur’anic narrations appear to have great significance and are discussed in the article Qur'anic Accuracy vs. Biblical Error: The Kings and Pharaohs of Egypt.

Concerning Pharaoh, the Qur’an says:

Pharaoh said: "O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself." [Qur'an 28:38]

Then he (Pharaoh) collected (his men) and made a proclamation, Saying, "I am your Lord, Most High". [Qur'an 79:23-24]

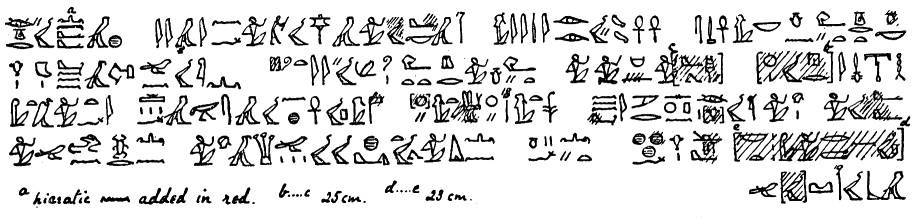

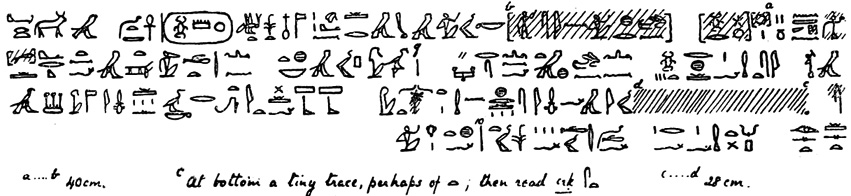

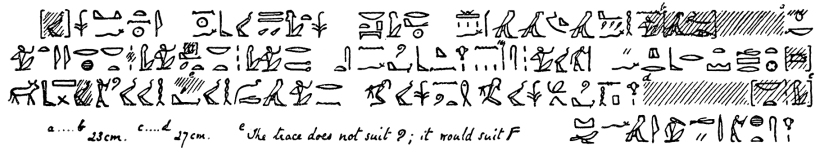

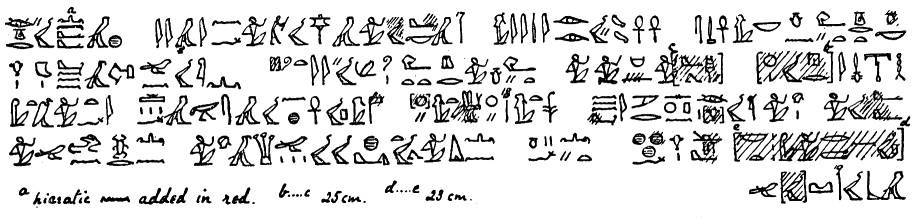

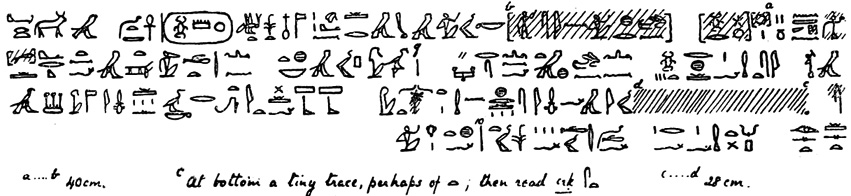

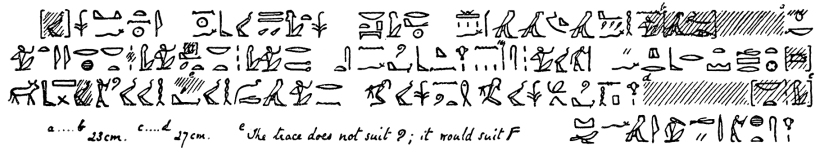

The issue of Pharaoh as the superlative god of Egypt is discussed more fully in the article Pharaoh And His Gods In Ancient Egypt. We will touch upon this issue briefly here. God says in the Qur’an that Pharaoh addressed his chiefs by saying that he knows for them of no god but himself [Qur’an 28:38]. This statement can be verified by simply checking the views of the king’s subjects, i.e., court officials. What the subjects of the Pharaoh could expect of the ruler in accordance with the Egyptian theory of the kingship is very well summed up in a quotation from the tomb autobiography of the famous vizier Rekhmere of Tuthmosis III from the18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period. The inscription occupies the southern end-wall of the tomb of Rekhmere and comprises 45 lines of hieroglyphs painted in green upon a plaster surface.

Rekhmer's relation to the king (II. 16-19)

... What is the king of Upper Egypt? What is the king of Lower Egypt? He is a god by whose dealings one lives. [He is] the father and mother [of all men]; alone by himself, without an equal ...[136]

According to Rekhmere, the king of Egypt was a god by whose decree one lives. He is alone, has no equal and takes care of his subjects like a parent. This affirms that the officials in ancient Egypt considered Pharaoh to be the supreme god, thus indirectly confirming the statement made by Pharaoh to his chiefs, as read in the Qur’an, that he knew of no god for them but himself. Furthermore, Rekhmere adds that the ruler like Egypt had divine qualities such as omniscience and a wonderful creator.

The audience with Pharaoh (II.8 - 10)

.... Lo, His Majesty knows what happens; there is indeed nothing of which he is ignorant. (9) He is Thoth in every regard. There is no matter which he has failed to discern...... [he is acquainted] with it after the fashion of the Majesty of Seshat (the goddess of writing). He changes the design into its execution like a god who ordains and performs.....[137]

Furthermore, the king was recognized as the successor of the sun-god R, and this view was so prevalent that comparisons between the sun and king unavoidably possessed theological overtones. The king’s accession was timed for sunrise. Hence the vizier Rekhmere explained the closeness of his association with the king in the following words:

Rekhmer's as a loyal defender of the king (II. 13-14)

... I [saw] his person in his (real) form, R the lord of heaven, the king of the two lands when he rises, the solar disk when he shows himself, at whose places are [Black] Land and Red Land, their chieftains inclining themselves to him, all Egyptians, all men of family, all the common fold...... ..... lassoing him who attacks him or disputing with him...[138]

Rekhmere also adds that the whole of Egypt followed the ruler of Egypt, whether chieftains or common folk. That the Pharaoh was indeed considered the superlative god in ancient Egypt is a common knowledge. The Encyclopaedia Britannica informs us that the term ‘Pharaoh’ originally referred to the royal residence, and was later applied to the king during the New Kingdom period (1539-1292 BC), and, that the Pharaoh was indeed considered a god in ancient Egypt

Pharaoh (from Egyptian per 'aa, "great house"), originally, the royal palace in ancient Egypt; the word came to be used as a synonym for the Egyptian king under the New Kingdom (starting in the 18th dynasty, 1539-1292 BC), and by the 22nd dynasty (c. 945-c. 730 BC) it had been adopted as an epithet of respect. The term has since evolved into a generic name for all ancient Egyptian kings, although it was never formally the king's title. In official documents, the full title of the Egyptian king consisted of five names, each preceded by one of the following titles: Horus; Two Ladies; Golden Horus; King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Lord of the Double Land; and Son of Re and Lord of the Diadems. The last name was given him at birth, the others at coronation.

The Egyptians believed their Pharaoh to be a god, identifying him with the sky god Horus and with the sun gods Re, Amon, and Aton. Even after death the Pharaoh remained divine, becoming transformed into Osiris, the father of Horus and god of the dead, and passing on his sacred powers and position to the new Pharaoh, his son.

The Pharaoh's divine status was believed to endow him with magical powers: his uraeus (the snake on his crown) spat flames at his enemies, he was able to trample thousands of the enemy on the battlefield, and he was all-powerful, knowing everything and controlling nature and fertility. As a divine ruler, the Pharaoh was the preserver of the God-given order, called ma'at. He owned a large portion of Egypt's land and directed its use, was responsible for his people's economic and spiritual welfare, and dispensed justice to his subjects. His will was supreme, and he governed by royal decree.[139]

Concerning Pharaoh, Nelson's Illustrated Bible Dictionary says:

The Egyptians believed that he was a god and the keys to the nation's relationship to the cosmic gods. While the Pharaoh ruled, he was the son of Ra, the sun god and the incarnation of Horus. He came from the gods with divine responsibility to rule the land for them. His word was law, and he owned everything. When the Pharaoh died, he became the god Osiris, the ruler of the underworld...[140]

However, it was claimed by F. S. Coplestone that the alleged source of Pharaoh claiming divinity, as mentioned in the Qur’an, was Midrash Exodus Rabbah.[141] This midrash says:

Pharaoh was one of the four men who claimed divinity and thereby brought evil upon themselves.... Whence do we know that Pharaoh claimed to be a god? Because it says: 'My river is mine own, and I have made it for myself' (Ezek. xxix, 3).[142]

There are a number of problems, one of them quite serious, concerning Midrash Exodus Rabbah being the source of the Qur’anic verses. Firstly, Midrash Exodus Rabbah has been dated several centuries after the advent of Islam. Midrash Exodus Rabbah is composed of two different parts. The first part (ExodR I) comprises parashiyot 1-14 and is an exegetical midrash on Exodus 1-10 (11 is not treated in Exodus Rabbah). The Pharaoh claiming divinity comes from ExodR I part of the midrash. The second part (ExodR II) with parashiyot 15-52 is a homiletic midrash on Exodus 12-40, which belongs to the genre of the Tanhuma Yelammedenu midrash. Leopold Zunz, who does not divide the work, dated this whole midrash to the 11th or the 12th century CE.[143] Herr, on the other hand, considers the ExodR II to be older than ExodR I, which in his opinion used the lost beginning of the homiletic midrash on Exodus as a source. For the dating of ExodR I, he conducts a linguistic analysis and judges this part to be no earlier than the 10th century CE.[144] Similarly, Shinan opines that the origin of ExodR I is from the 10th century CE.[145] The Qur’an could not have used a source that had not yet been compiled until hundreds of years later. Secondly, the midrash simply interprets the verse from the book of Ezekiel and claims that the verse implies Pharaoh claiming divinity. The Qur’an, on the other hand, explicitly states that the Pharaoh proclaimed himself to be the superlative god.

تحمَّلتُ وحديَ مـا لا أُطيـقْ من الإغترابِ وهَـمِّ الطريـقْ

اللهم اني اسالك في هذه الساعة ان كانت جوليان في سرور فزدها في سرورها ومن نعيمك عليها . وان كانت جوليان في عذاب فنجها من عذابك وانت الغني الحميد برحمتك يا ارحم الراحمين

Thread Information

Users Browsing this Thread

There are currently 1 users browsing this thread. (0 members and 1 guests)

Similar Threads

-

By فداء الرسول in forum Slanders Refutation

Replies: 1

Last Post: 03-03-2013, 11:06 PM

-

By مطالب السمو in forum English Forum

Replies: 0

Last Post: 14-09-2012, 06:14 AM

-

By nemogh in forum English Forum

Replies: 2

Last Post: 10-05-2012, 06:57 PM

-

By شبكة بن مريم الإسلامية in forum English Forum

Replies: 0

Last Post: 19-10-2009, 11:54 AM

-

By اسد الصحراء in forum English Forum

Replies: 0

Last Post: 30-03-2006, 02:25 PM

Tags for this Thread

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks